Initially published in french by Basta!.

What do Cristiano Ronaldo, the Real Madrid and Portuguese national team star, who is playing the Euro 2016 in France, and a Vietnamese garment factory worker have in common? A brand: Nike. The former has a sponsorship deal worth around 25 million euros a year to wear shoes and jerseys carrying the Nike logo. The latter makes these same shoes and jerseys for a salary of about 170 euros a month [1], an income that is far below the “living wage” required to meet the basic needs (housing, energy, drinking water, food, clothing, health, education) of a Vietnamese family.

Select a tab at the bottom – National teams (France, Germany, Spain, Italy), clubs (Manchester United, Bayern Munich, FC Barcelona, Paris Saint-Germain) or players (Lionel Messi, Paul Pogba, Cristiano Ronaldo) – then scroll with the arrows to find out how many workers could be paid with the same amount of money as Nike, Adidas or Puma’s sponsorship contracts (source: Basic).

The imbalance is enormous: the money involved in the sponsorship contract between Nike and Cristiano Ronaldo would allow 19,500 Vietnamese workers labouring in the factories of Nike subcontractors to be paid a living wage (as estimated by the Asian Floor Wage Alliance, a coalition of Asian trade unions and non-governmental organizations [2]), for a whole year. “These shocking figures are an indictment of the business model of those global sportswear multinationals: escalating marketing and communications expenses, and prioritisation of shareholders’ interests, with no real benefits for the workers who contribute to their prosperity,” says Nayla Ajaltouni, from the collectif Éthique sur l’étiquette (Clean Clothes Campaign France), a coalition of French NGOs and trade unions dedicated to promoting human rights in the workplace.

Skyrocketing dividends and marketing expenses

Such is the paradox of the sportswear industry and its major corporations, Nike, Adidas and Puma, which together account for more than 70% of the global footwear and sportswear market. Marketing and sponsorship expenses, as well as dividends, have been steadily increasing, while the salaries paid by their subcontractors in Asia (mostly in China, Vietnam and Indonesia) have remained desperately low. In a decade, dividends paid to Nike shareholders have jumped 135%, approaching three billion euros in 2015. Those paid by Adidas increased by 66%, to just over 600 million euros last year.

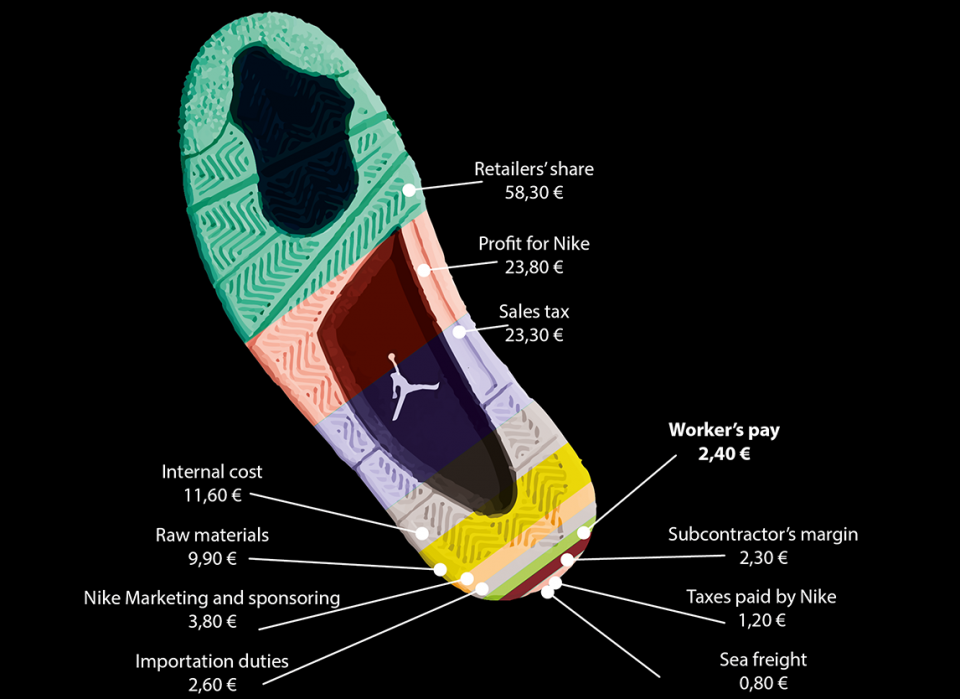

Éthique sur l’étiquette estimates that of the hundred euros a consumer spends on a pair of Nike shoes, only two euros go to the worker who made them. Of the 85 euros spent on an Adidas jersey, the figure is even lower: about 60 cents. The direct profits made by the brands are around 25 euros. The share devoted to workers pay is lower than that dedicated to sponsorship and marketing, which is about 3 or 4 euros per piece of sportswear. Sponsorship budgets, like dividends, have also sharply increased in recent years.

Breakdown of the amount paid for a Nike Air Jordan shoe: worker pay represents only 2.4 euros (source: Basic).

Wages kept at rock bottom

Sponsorship contracts with ten leading European football teams (such as Manchester United, Barcelona and Milan for Nike, or Real, Bayern and Chelsea for Adidas.) alone accounted for 400 million euros in 2015, up by a third since 2013. This extravagance is well known. But what is less known is the discrepancy between such business practices and these corporations’ eagerness to tout their “social responsibility”. Their relentless pursuit of the cheapest production costs deprives those who manufacture these sneakers and jerseys of any hope of better wages.

Adidas employs about 400,000 workers in China, Vietnam and Indonesia. In a document on its “responsible practices”, the German supplier “recognises the importance of respecting and promoting human rights globally. We also believe that the private sector can play a constructive role in advancing this goal.” Nike also seems concerned about these issues: “Workers’ wage concerns are among the priorities identified during our audits in factories. We believe this is an important objective and have spent several years investigating the salaries that workers earn in our suppliers’ factories.”

“Audits” and PR

It may seem that the most blatant abuse tarnishing the sports industry’s reputation is now a thing of the past. Twenty years ago, Nike was the first multinational in the garment sector to become the subject of international outrage, after photographs were published that showed Pakistani children squatting on bare floors, trying to sew footballs bearing its brand. Both Adidas and Nike were accused in the early 2000s of using Indonesian subcontractors that employed children working fifteen hours a day, for a monthly salary of less than 50 euros [3]. Since then, both companies have stepped up their social audits and indicators.

In 2011, six major international brands including Nike, Adidas and Puma signed an agreement with Indonesian employers and unions to guarantee freedom of association in all factories of their subcontractors in the country. In 2013, after being targeted by an international campaign, Adidas agreed to participate in the compensation of 2,800 Indonesian workers who had been brutally dismissed from one of its subcontractor’s factory, after its owner ran away. In 2014, several large garment brands including Nike, Adidas and Puma, asked the Cambodian government to respect the rights of workers fighting for a minimum wage.

Chinese wages now too high

Publicly, these corporations have been claiming that they are seeking to establish “long term partnerships” with their suppliers. In reality, the increasing pressure of marketing and sponsoring expenses and the relentless pursuit for the lowest production costs have largely prevented them from making good on these alleged intentions, as demonstrated by an analysis by Basic, an independent research organisation, commissioned by collectif Éthique sur l’étiquette.

This is vividly illustrated by the attitude of these multinationals towards their Chinese suppliers. Over ten years, the average annual salary in China has increased by a factor of 2.5, and the minimum wage has tripled. It is the only Asian country where the average wage is finally approaching the level of a “living wage” as defined by Asian civil society. Given how much they like to tout their social responsibility, one would think that multinational sportswear companies would welcome this development. They are in fact upset about it. In an internal document seen by Basic, Adidas voices its concern about “the end of low-cost China”. At Nike, an internal survey also deems the wage increases in China a “threat” to the “sustainability of added value”.

Welcome to Vietnam and Indonesia

Sportswear giants are now seeking this “sustainability of added value” – i.e., low wages in their subcontractors’ factories – elsewhere in Asia: mostly in Vietnam, and to a lesser extent in Indonesia and Cambodia, countries which rate poorly when it comes to International Labour Organisation standards. According to 2015 ILO data, nearly ninety percent of Vietnamese factories do not comply with the country’s official legislation on paid leave. Almost a third of Indonesian factories pay their workers less than the local minimum wage, which is 80 euros a month. In two thirds of factories, working hours regularly exceed legal limits. The average wage is much lower than the living wage: 102 versus 209 euros in Indonesia, 174 versus 247 euros in Vietnam. In China, the average wage, at 400 euros, is closer to a genuine living wage (460 euros).

Yet it is this country that multinational corporations like Adidas and Nike are seeking to escape. By 2020, the percentage of Adidas T-shirts made in China is expected to fall from 33% to 12%, with the production shifting primarily to Vietnam, Cambodia and Indonesia, according to the internal document seen by Basic. The percentage of Adidas shoes made in China will also drop from 23% to 15%, production again moving to Vietnam, Indonesia and post-dictatorship Myanmar. Having a minimum wage that is “lower than China” is among Nike’s top criteria for choosing where to source its production. “Now that progress has finally been made in China, with improved wages and labour conditions, these brands say, it’s too expensive, we’re leaving,” says Laurent Maeder, an auditor for a Swiss consultancy working for the garment industry.

Perpetual Race to the Bottom

For Nayla Ajaltouni, of collectif Éthique sur l’étiquette, “If Nike and Adidas have been among the first global corporations to develop social responsibility policies, it’s because they were among the first to be put on the spot. What they have done is seek to minimize reputation risks by being a bit more transparent about their supply chain. Recent developments have demonstrated the limitations of this approach. Given their profit margin, these brands could very well afford to buy products made under decent labour conditions, but they continue to seek the lowest cost possible.”

This is also the effect of the unchecked inflation of advertising and sponsorship costs in sportswear companies. The 400 million euros sponsorship contracts they have signed with the ten major European football clubs in 2015 would be sufficient to pay a living wage to 160,000 Indonesian workers and allow them a decent life. These multinationals have developed very precise management tools to monitor the cost of manufacturing a shoe, from the sole to the laces, including the profit margin and the workers’ pay. “This is a negotiation and cost optimisation tool that proves their ability to control their entire supply chain. Nothing would prevent them from using this tool to calculate the purchase cost that would enable a decent living wage. But they’re not interested,” says Christophe Alliot of Basic. We contacted Nike and Adidas, asking them to explain their policies, but both firms declined our request for an interview.

Gold and glitter in the shop windows, darkness in the back room

Beyond the issue of wages, working conditions at subcontractors are often problematic, particularly in terms of workers’ exposure to chemicals. “Chemical products with adverse health effects are used to give certain specific qualities to the products, particularly shoes,” says Laurent Maeder. UV-resistant dyes, perfluorocarbons (PFCs) for waterproofing, anti-bacterial silver ions, anti-mosquito agents . . . These are just a few of the chemicals that were detected in a series of Adidas and Nike sports shoes analysed by Greenpeace for the 2014 World Cup [4].

Both companies later joined the “Blue Sign” programme, which seeks to ban all toxic products from supply chains. “But out of the millions of products they sell, what is the outsourced share that escapes certification mechanisms?” wonders Maeder. “They are so big, with such massive production volumes, that it becomes difficult to check 100% of production.”

Twenty years after the first controversies about Nike, the sportswear industry is still struggling to break away from a business model that prioritises the glitz of advertising and sponsorship at the expense of its workers’ wages and working conditions. The official Euro 2016 ball, commissioned by UEFA, will be manufactured by Adidas in Pakistan, as it was for the 2014 World Cup . . .

Ivan du Roy

Infographics: Germain Lefebvre

This article was published in collaboration with Alternatives économiques, as part of a joint project in economic and social investigative journalism, supported by the Charles Leopold Mayer Foundation.